The U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled on Tuesday that corner crossing is legal.

“The district court was correct to hold that the Hunters could corner-cross as long as they did not physically touch Iron Bar’s land,” the appeals court found.

The appeals court summarized the case:

In the fall of 2020, Bradley Cape, Zachary Smith, and Phillip Yeomans

traveled from Missouri to Elk Mountain to hunt elk. Upon arriving in Wyoming, the

Hunters drove down the public Rattlesnake Pass Road to BLM Section 14, where

they parked and set up their camp. Using onX Hunt—a GPS mapping tool that helps

users find property lines and determine land ownership—they navigated to the

corners of public land overlaying Elk Mountain. These corners are physically

denoted by a steel United States Geological Survey marker cap driven into the

ground. Once at the cap, the Hunters “corner-crossed” and stepped directly from the

corner of one public parcel to the corner of the other. The Hunters never made

contact with the surface of Iron Bar’s land, but they did momentarily occupy its

airspace.

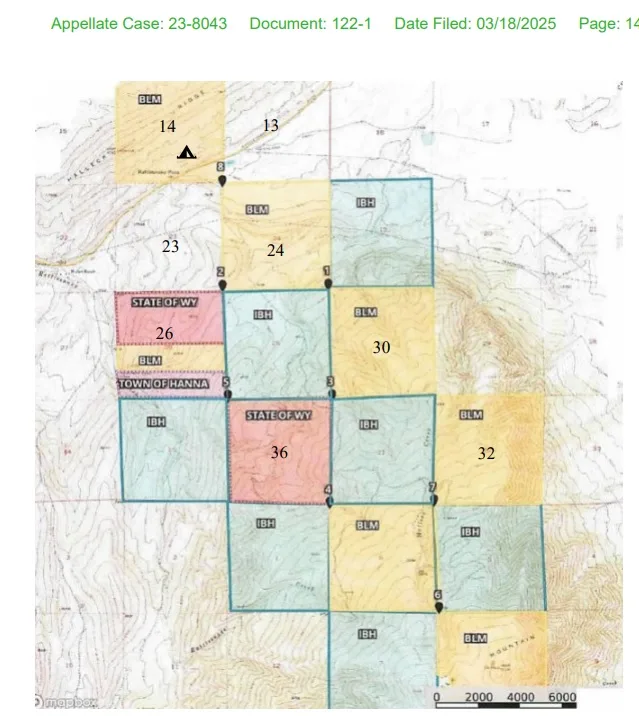

Over the next several days, they hunted on public parcels—Sections 24, 26,

30, and 36—denoted on the following map:

This map was used by the district court. Iron Bar Holdings, LLC v. Cape,

674 F. Supp. 3d 1059, 1064 (D. Wyo. 2023). Iron Bar owns Sections 13 and 23, and

all sections labeled IBH. The Hunters’ tent is indicated in Section 14. The

dropped pins represent corner-crossing points.

Iron Bar is not friendly to corner-crossers. In seeking to prohibit cornercrossing, Iron Bar had erected signposts over the United States Geological Survey

marker denoting the corner of Sections 13, 14, 23, and 24.

There were no other posts, fencing, or buildings

within a quarter mile of the corner.

The Hunters could not fit between the signposts and under the chain to cornercross, but they were undeterred by this odd barricade: “one by one, each grabbed one

of the steel posts and swung around it, planting their feet only” on Sections 14 and

24, but passing through the airspace above Iron Bar’s Sections 23 and 13.

(cleaned up). There is no showing that the Hunters did any damage to Iron Bar’s

property.

But the Hunters would soon discover that this was not Iron Bar’s only cornercrossing deterrence strategy.

Prior to 2020, [Iron Bar] instituted an ongoing practice of

having its employees confront or interact with a “suspected

trespasser” found on or near [its] property, even if the

person was found while on public land. The suspected

trespasser is instructed to leave, but if they resist, [Iron Bar]

will contact local law enforcement, including the Wyoming

Game & Fish Department, to seek a criminal trespass

citation or other prosecution. And if in [Iron Bar’s] view

law enforcement takes insufficient action on the matter, [it]

will continue to contact law enforcement to push the matter

and will also contact the local prosecutor’s office to request

criminal prosecution.

Iron Bar learned of, but did not approve of the Hunters’ presence. Consistent

with its policy, Iron Bar’s property manager found the Hunters on Elk Mountain

public land and requested that they leave the area. The Hunters refused, so the

manager contacted law enforcement. The responding sheriff, however, did not issue

a warning or citation after the Hunters explained that they had merely corner-crossed.

The Hunters completed their hunting trip and returned home without further incident.

F. The 2021 Hunt

The Hunters returned to the area in 2021. This time, they brought a steel

A-frame ladder to avoid even touching Iron Bar’s signposts:

Iron Bar’s staff proved much more inhospitable this time around. The

property manager and another employee confronted the Hunters multiple times.

They also interfered with the Hunters’ activities by driving motorized vehicles across

public parcels to scare away game. As in 2020, there is no evidence the Hunters

made physical contact with or damaged Iron Bar’s property. Id. at 1069. When the

Hunters refused to leave, the manager contacted the Wyoming Game and Fish

Department and the local sheriff’s office. Both refused to take action.

The manager resorted to contacting the local prosecuting attorney’s office,

who agreed to prosecute the Hunters for criminal trespass. That office instructed the

sheriff’s office to write the Hunters citations for criminal trespassing, and directed

the Wyoming Game and Fish Department to instruct the Hunters to leave and not

reenter the public lands at issue. The Hunters went all the way to a jury trial on the

Wyoming criminal trespass charges, but were ultimately acquitted.

That same day, Iron Bar served the Hunters with a lawsuit for civil trespassing,

alleging $9 million in damages owing to alleged diminution of its property value.

Following discovery, the parties cross-moved for summary judgment. The district

court denied Iron Bar’s motion and granted the Hunters’ motion as to “all claims of

trespassing involving [Appellant]s’ corner-crossing.” Id. at 1080. In reaching this

outcome, the district court held “corner-crossing on foot in the checkerboard pattern

of land ownership without physically contacting private land and without causing

damage to private property does not constitute an unlawful trespass.”