From the time he was twelve until he was ninety-nine, William Henry Jackson was all about photography. After serving in the Civil War, he headed west from New York and settled in Omaha, Nebraska, where he and his brother Edward opened a portrait studio. But Jackson wasn’t really into portraits. Instead, he said, “Portrait photography never had any charms for me,” so he took his camera to the rooftops, then the hilltops, and eventually into the wilds of the American West. The more he explored, the more success he had—and the more he loved capturing the landscapes around him.

In 1870, Jackson joined geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden on an expedition through Wyoming, along the Green River, and into Yellowstone Lake. His photos were the first ever published of Yellowstone, and partly because of them, the area became the first U.S. national park in 1872. He also became the first person to photograph the ancient Native American dwellings in Mesa Verde, Colorado.

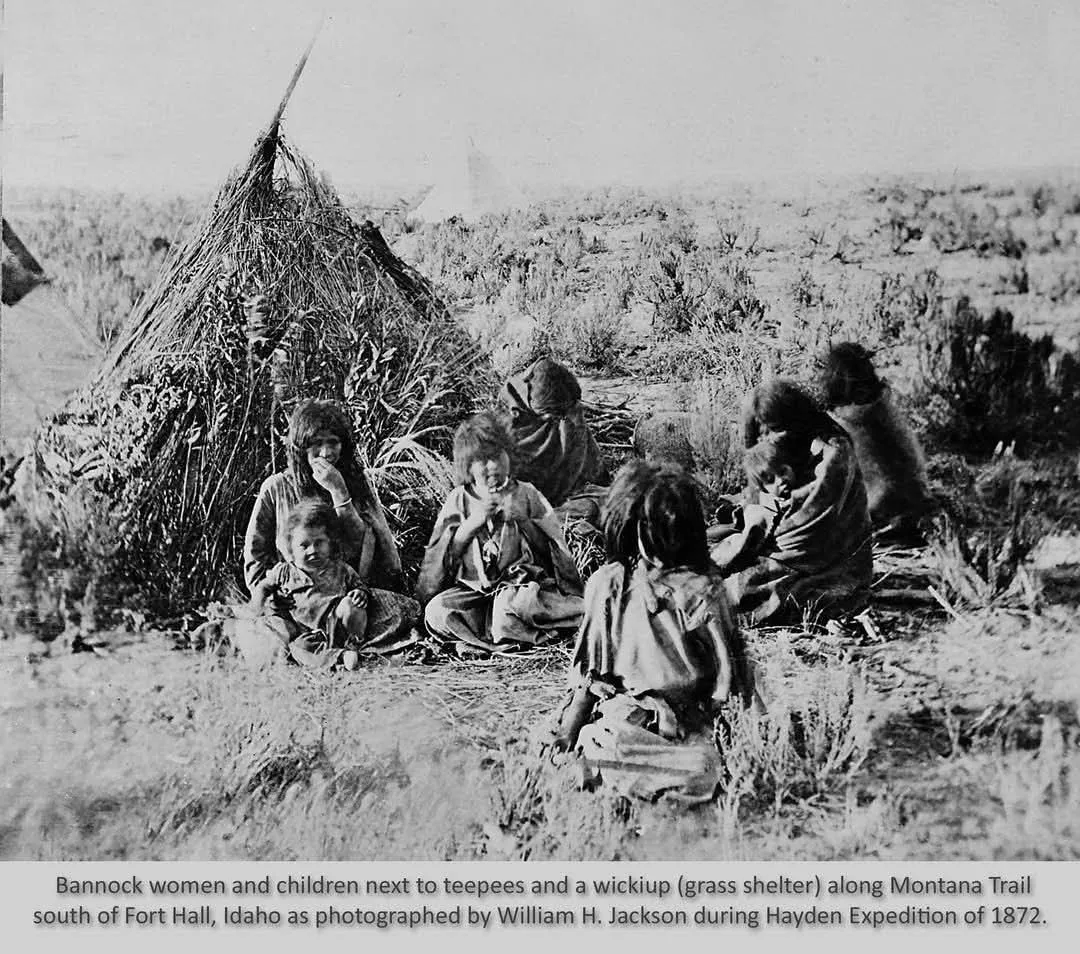

By the time he settled in Denver, Jackson was a well-known commercial landscape photographer, and his photos were eventually turned into popular postcards. One of his most striking shots, taken in 1872 along the Montana Trail near Fort Hall, Idaho, shows a group of Bannock women and children by their teepees and a wickiup. There’s definitely some tension in the air—while the women turn away from the camera, the youngsters eye it with suspicion. Understandably, the big, unfamiliar contraption probably didn’t seem too welcoming, especially being pointed in their direction.

This photo, taken during the Hayden Expedition, is one of the earliest glimpses of Eastern Idaho’s people and landscapes. It’s a moment frozen in time, silently telling a story that speaks louder than words.

Sources: Getty.edu, Ross Shiro